Have Trade “Preference” Programs Kept Up with the Times?

The times, they are a-changing

Much has changed since the so-called “generalized system of preferences” was created in the 1970s to help promote economic development among the poorer WTO member countries. There’s little economic data to demonstrate the programs have accrued significant benefits. The programs themselves have become laden with conditions for eligibility, exceptions, reviews, and mandatory graduation. The cost of participating in them can even be prohibitive for developing country exporters.

Nearly two decades after the “Doha Development Round” of negotiations kicked off in the WTO, perhaps it’s time to revisit the core question of whether creating exemptions for developed country members to offer one-way market access while enabling developing countries to “free ride” is serving either group – or the global trading system – very well.

Is there such a thing as a free ride?

The concept of creating a generalized, non-reciprocal system of preferences for developing countries dates to a resolution taken at a 1968 meeting in New Delhi of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Many countries were newly independent. “Infant industry” protection and import-substitution approaches were popular in the 1960s, but producers were limited to their home markets, giving rise to the idea that preferential access to export markets would advance economic development goals. Preferences were intended to help developing countries “increase their export earnings, promote their industrialization, and accelerate their rates of growth.”

To provide a legal basis for one-way preferences, the parties to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) needed to figure out how to enable some of its members to legitimately discriminate by offering better market access to a subset members. After all, non-discrimination is the cornerstone of the GATT and subsequent trade agreements. In 1979, they adopted a specific and enduring exception – known as the “Enabling Clause” – for this purpose.

“Enabling” discrimination

The Enabling Clause effectively allows WTO members create national programs designed to eliminate tariffs or offer expanded market access to qualifying developing countries and to do so without according the same treatment to other members. Beneficiary countries are not required to reciprocate.

The United States, the European Union (EU), Japan, Canada, New Zealand, even Russia, maintain programs called under the Generalized System of Preferences or GSP. They are referred to as generalized because the programs are also intended to avoid discriminating among developing country beneficiaries themselves. But enabling discrimination has predictably had positive and negative consequences.

Over the years, sponsoring countries have designed programs specifically for members of a geographical grouping, such as Europe’s program for Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific or U.S. programs tailored to Sub-Saharan Africa, the Andean countries, or Caribbean Basin countries. Greater benefits may be offered to the least developed countries. Some programs offer benefits according to whether eligible countries enforce worker rights, cooperate in combating drug production and terrorism, or improve protection of intellectual property rights.

For example, the EU program has three tiers: “standard” access for 23 low-income or middle-income countries who receive duty-free treatment on 66 percent of the EU’s tariff schedule, a GSP+ version wherein the 10 beneficiaries must first ratify and implement standards for human and labor rights, environmental protections and good governance to qualify, and an Everything but Arms version that offers complete duty-free access to 49 least-developed countries.

These approaches have drawn criticism over the years from developing countries themselves. India and other members have even challenged these programs in the WTO, arguing the programs discriminate among developing country beneficiaries. WTO panels have green-lighted such differentiation under the GATT Enabling Clause as long as the member granting the benefits offers the same benefits to “similarly situated” developing country members with respect to the development, financial, and trade needs to which the additional tariff benefits are meant to apply.

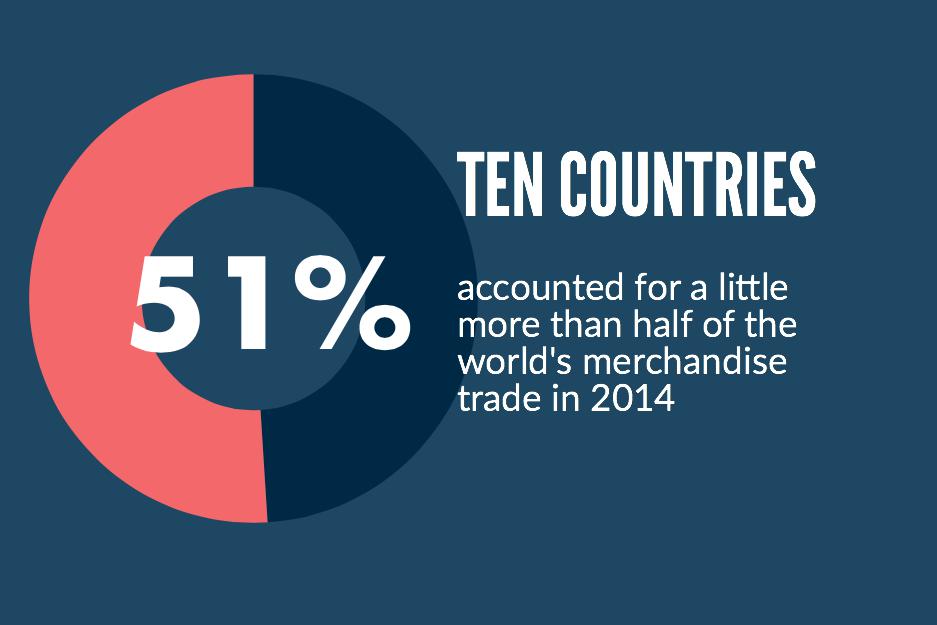

Is this a big deal?

The U.S. GSP program was authorized through the Trade Act of 1974. Today, 121 developing countries and territories are beneficiaries of U.S. GSP. The program covers more than 3,500 products that beneficiary developing countries can import duty-free. 44 of the least developing countries among the beneficiaries also qualify for another 1,500 products. The numbers sound big, but less than 3 percent of total U.S. imports entered under the program. Though small in scale, the benefits of tapping into the United States and other mature markets is valuable for many developing country exporters.

In 2017, $21.2 billion worth of goods were imported duty-free using the GSP program. In total, however, the U.S. imported $215 billion from all GSP countries, so only about 10 percent entered under GSP.

Limits and Conditions

Part of the explanation for these low numbers is that nearly half of goods we import enter duty-free on a Most Favored Nation basis – meaning, we offer a tariff rate of zero to every WTO member for those products, making those goods cheaper for Americans to buy. Among remainder of goods that could be part of the duty-free program, some are off limits due to concerns about competition with domestic producers. These import-sensitive sectors are unfortunately often those where developing country producers could export more without the tariff as an impediment – often textiles, apparel, or value-added agricultural products.

In other cases, the origin requirements are too hard or costly for developing country producers to meet. A more mundane reason for eschewing the program is lack of awareness about it by developing country exporters or inability to navigate the bureaucracy and paperwork to qualify.

The biggest beneficiaries are the biggest emerging markets, engendering some debate over whether and how to appropriately limit or taper off their access to the program as these countries become wealthier. Most programs have built-in triggers for “graduation” from the program when countries reach a certain income level or mechanisms to remove access to product categories when a beneficiary become competitive in global markets.

Carrots and Sticks

Governments sponsoring GSP programs create mandatory and discretionary criteria for eligibility, some of which reflect a growing desire to create reciprocal obligations. The United States can consider whether a beneficiary country is committed to providing “reasonable and equitable access to its market.”

The Administration is required to provide annual reports to Congress on the operation of the program, including whether beneficiaries are meeting such obligations. Last year, the Administration accepted two industry petitions and added its own grievances to a review of whether India is meeting the market access criterion of GSP eligibility, recently proclaiming that India has 60 days to make improvements or get kicked out of the program. The United States is also reviewing Indonesia’s treatment of U.S. services and investment, as well as worker rights in Kazakhstan in response to a petition from the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). U.S. pork producers petitioned for a review of Thailand’s eligibility in light of restrictions on access to its market.

GSP can be used to punish or reward good behavior. For example, the administration partially reinstated Argentina’s use of preferences in December 2017 after Argentina made commitments to resolve arbitral disputes with U.S. companies and improve market access for U.S. agricultural products, withholding some benefits pending improvements to intellectual property protections. Gambia saw its eligibility for preferences restored after efforts to strengthen the rule of law and improve its human rights record. Swaziland’s benefits were restored after it met all of the prescribed U.S. benchmarks for freedoms of assembly. President Trump also ended Burma’s 27-year suspension in recognition of that country’s move to more democratic governance.

If Everyone is Special, No One is Special

Since 2014, the EU has graduated upper-middle income beneficiaries and launched an initiative to establish reciprocal deals with developing country trading partners in an effort to move away from one-way preferences. Japan and Canada have also graduated upper-middle income countries and those that have achieved a 1 percent or greater share of world exports for two consecutive years. The United States graduates any high-income country (those with per capita of $12,055 or more). President Obama graduated Russia in 2014, and determined in 2015 that Seychelles, Uruguay and Venezuela were to be graduated in January 2017.

Is all this reflective, or an extension of, a broader debate in the WTO about who’s developing versus developed? And might some resolution of that debate in turn impact how countries administer their preference programs – likely so.

Some agreements negotiated during the GATT Tokyo Round that ended in 1979 were voluntary to join. The option had the effect of creating separate tracks: one for developed country commitments and another for developing countries to opt out. The Uruguay Round ending in 1994 was the first set of multilateral talks to bring developing countries more fully into the system but with “special and differential treatment” in the form of exceptions, longer transitions, or other flexibilities with regard to implementing commitments.

The Doha Development Round launched in 2001 was called the Doha Development Round but it collapsed because the core commitments were hollowed out by an emphasis on exceptions. Its failure spurred a rash of regional trade agreements outside the WTO and “plurilateral” negotiations that, whether they result in agreements inside or outside the WTO, will probably not include the least developed or most developing countries. Liberalization and market access will expand among mature and higher-income developing countries, leaving the remaining developing countries on the margins and effectively eroding the value of benefits under preference programs. You can’t offer better than duty-free.

Time to Rethink?

Trade among developing countries is growing faster than trade between developed and developing countries. In 2004, after the Doha Round was launched, the World Bank conducted a study on the possible gains from developing country liberalization in the Doha Round and found that nearly 70 percent of tariffs paid by developing countries are paid to other developing countries, and those tariffs tend to be three times higher than the average tariff in developed markets.

That’s a problem that preference programs can’t solve.

So, is it time to rethink? If most new trade agreements do not involve developing or the least developed countries, these countries could remain on the margins of global trade.

Whether preference programs help, they are at best insufficient for achieving development goals. The benefits for accelerating trade and economic growth through multilateral commitments in the WTO likely outweigh the limited and diminishing benefits of generalized preference programs.

Resources to learn more:

Congressional Research Service Report: Generalized System of Preferences (GSP): Overview and Issues for Congress, Updated January 8, 2019

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative current GSP reviews

UNCTAD Handbooks on National GSP Programs

Andrea Durkin is the Editor-in-Chief of TradeVistas and Founder of Sparkplug, LLC. Ms. Durkin previously served as a U.S. Government trade negotiator and has proudly taught international trade policy and negotiations for the last fifteen years as an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University’s Master of Science in Foreign Service program.