Wave of Global Sand Trade May Be Depleting Beaches

Not just sand castles

It’s September, which officially marks the end of summer. Kids have headed back to school and the sandcastles are long since washed away from the shore. But you’re never really far from the beach. It’s actually all around you since most of the infrastructure in your homes, schools and offices is made of sand.

Sand is a critical component in many of the products we depend on every day: glass, concrete, asphalt, computer chips, and more. We use up to 50 billion tons of it every year, making it the second-largest resource extracted and traded by volume each year, behind water. Despite our necessity for sand, there are no international conventions that specifically regulate the extraction, use and trade of land-based sand. As demand outpaces supply, shortages have even led to illicit trade in sand in some regions of the world.

The many uses of sand

Sand is made of rocks that have eroded over thousands of years. There are many different types of sand and each has its own purpose. Sand from riverbeds is the most desired for construction materials like cement and asphalt. Silica sand from quartz is used for glass, ceramics and electronics. Marine sand is used for land reclamation. The list goes on.

Sand is also pivotal for oil and gas companies for hydraulic fracking. Oil companies mix silica sand (also called “frac sand”) with water and shoot it into shale rocks to break them apart and access the oil and natural gas inside. Companies recently discovered that using more silica sand makes the fracking process more efficient. This has led to increased U.S. consumption of industrial sand and gravel, up 13 percent to 110 million tons consumed in 2018.

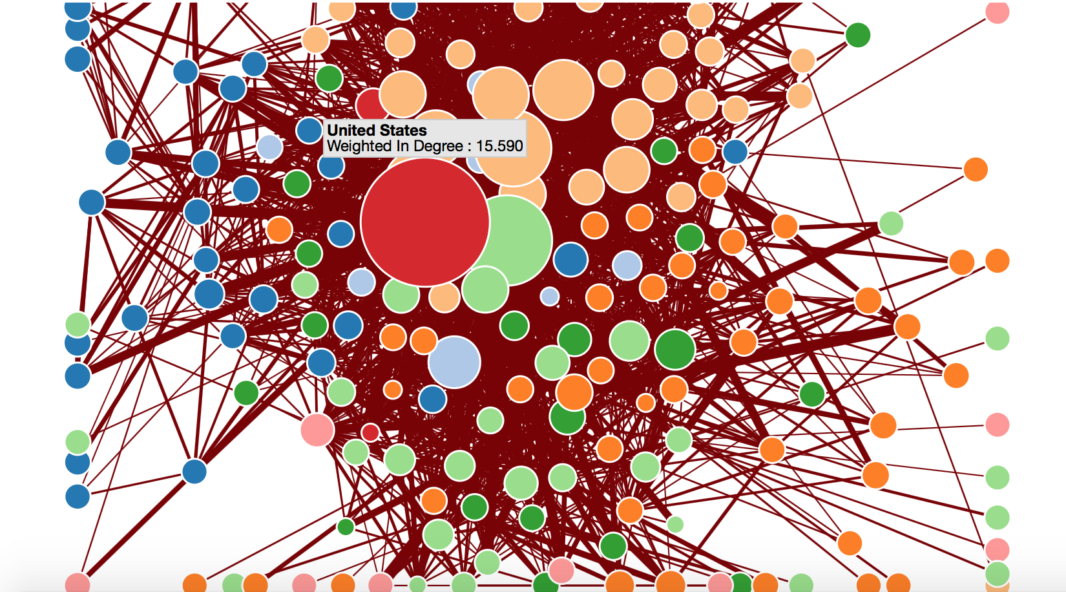

Despite increased consumption of sand, the United States is still the world’s top exporter, responsible for nearly 30 percent of the world’s natural sand exports in 2018. Top destinations for U.S. sand exports include Canada, China, Japan and Mexico.

As cities grow, so does demand for sand

Demand for sand is expected to increase in the coming years, especially in developing countries faced with increasing populations, urbanization and economic growth. Nearly two-thirds of global cement production happens in China and India, reflecting their rapidly urbanizing populations. China alone produced more cement last year than the rest of the world combined.

In the past, sand trade has stayed mostly regional because it’s heavy to transport. But in the coming years, as demand outpaces supply, international trade in sand is forecasted to grow at 5.5 percent each year, according to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). Resource-constrained countries will be particularly dependent on sand imports to meet the needs of their rapidly growing urban areas.

Singapore is the world’s largest sand importer, importing an estimated 517 million tons of sand over the last 20 years. Most of this sand came from its Southeast Asian neighbors including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Cambodia. Singapore has used this sand to increase its land area by 20 percent over the last 40 years, but Singapore’s thirst for sand has led to tensions in the region.

According to the UNEP, sand exports to Singapore were reportedly responsible for the disappearance of 24 Indonesian sand islands. Indonesia formally banned sand exports to Singapore in 2007. In the last two years, Cambodia and Malaysia have also banned sea sand exports citing environmental concerns. Malaysia’s 2018 ban will likely have a big impact on Singapore, since Malaysia was the source for 96 percent of Singapore’s sand imports last year.

Another top importer of sand in the region is the United Arab Emirates, which is surprising given its prime desert location. Desert sand, however, is not useable for construction purposes since desert winds make it too fine and smooth. The UAE is thus dependent on sand imports to continue making roads, buildings and other infrastructure in Dubai. The UAE imported over two million tons of natural sand in 2018, according to the International Trade Centre.

Sand mafias are stealing entire beaches

The growing need for sand has led to illicit sand trade and “sand mafias” in developing and emerging economies across the world. Stories abound of beaches disappearing overnight, rivers drying up and more.

In Morocco, an estimated 10 million cubic meters per year— about half the sand the country uses— is illegally stripped from its coast. The erosion has caused serious issues for the country’s tourism sector, as many buildings are now at risk from beach erosion due to illegal sand mining.

“Sand mafias” are another example of the perils of the illegal sand trade. Due to the increasing price of sand, organized crime surrounding it is also thriving, according to the UNEP. Activists who speak out against these sand mafias that illegally strip river beds and coasts in countries like India have been threatened and even killed, the organization says.

Likes grains in an hourglass

We may take sand for granted, but we’re extracting it far faster than nature can replenish it. Most major rivers across the world have already lost between 50 and 95 percent of their natural sand and gravel, the UNEP says. Matters are made worse by irrigation and hydroelectricity dams, which also reduce the natural amount of sediment flowing in rivers. These factors can cause serious environmental issues, including erosion, pollution, flooding and droughts.

Despite its importance worldwide, sand is one of the least regulated resources today. There are no international conventions regulating the extraction, use or that specifically govern trade in land-based sand. Rules for sand extraction are largely written at the national and regional levels, leading to a variation of standards and different levels of enforcement across the world.

The UNEP is trying to change this by calling on international organizations, national governments, private sector companies, civil society groups and local communities to come together and have a global conversation on sand extraction. As the world’s sand grains continue to slip quickly through the hourglass, the time for that conversation should be sooner rather than later.