Pomegranates are Symbolic Even for Trade

613 Seeds

It’s the Jewish New Year, a time for introspection and atonement and of course every Jewish holiday has its food customs. Celebrants dip apples in honey to symbolize hopes for a sweet year ahead. Pomegranates also figure in celebrations at this time of year. Its many seeds are associated with the 613 commandments in the Torah. Before eating the pomegranate seeds, Jews traditionally say, “May we be as full of mitzvot (commandments) as the pomegranate is full of seeds.”

The pomegranate is one of the seven species of Israel listed in the Torah, along with grapes, figs and dates. They’ve been cultivated throughout the Middle East for thousands of years and remain a staple in the cuisine. Outside the United States, consumers can enjoy dozens of varieties, from those with sweeter pink seeds to yellow-green Golden Globes. The only kind I’ve ever seen in my grocery store are the ruby red Wonderful variety, which make up 90 to 95 percent of the U.S. market.

Ancient and Modern Purveyor of Good Fortune

Pomegranates are drought tolerant so they can grow in tropical to warm climates, but they do best in regions with cool winters and hot, dry summers. They thrive throughout Latin America, southern Europe, Asia, Africa and Fresno, California. Due to this heartiness, there’s almost always a season for pomegranates somewhere in the world and – thanks to trade – we can enjoy them nearly all year-round. Recently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture approved imports of Peruvian-grown pomegranates, which U.S. retailers say won’t compete directly with California production because they’ll be harvested and shipped as California’s season ends.

Known to be a good source of antioxidants and vitamin C, pomegranates are more popular than ever, finding their way into juices, fruit strips and other processed foods. Higher demand has been especially great for exporters from developing countries. Pomegranate exports are even playing a role in moving farmers in Afghanistan from opium poppy or coca farms to growing legal as well as profitable crops.

Where efforts to shift into other crops have failed, the pomegranate holds promise. Afghan varietals are prized for being especially delicious, creating demand for Afghan farmers to supply pomegranates to buyers around the world. Last year, Afghan farmers exported nearly 23,000 tons of pomegranates, up 35 percent over the previous year. Non-profit organizations have provided startup seeds and planted hundreds of thousands of pomegranate saplings in Afghan fields. If successful, Afghan producers could also move into finished products like fruit bars. More than a symbol, pomegranates are a tangible vehicle for renewal in Afghanistan.

Sowing Trade Seeds

Although pomegranates no longer seem “exotic” to us, Americans are increasingly open to trying new varieties of fruits and vegetables in pursuit of innovative flavors, in response to health trends, and out of affinity for local growers who often produce heirloom and other varieties we can’t find in the grocery store. To enjoy a variety of foods – and importantly, to sustain basic crop production – growers must have access to a variety of high-quality seeds.

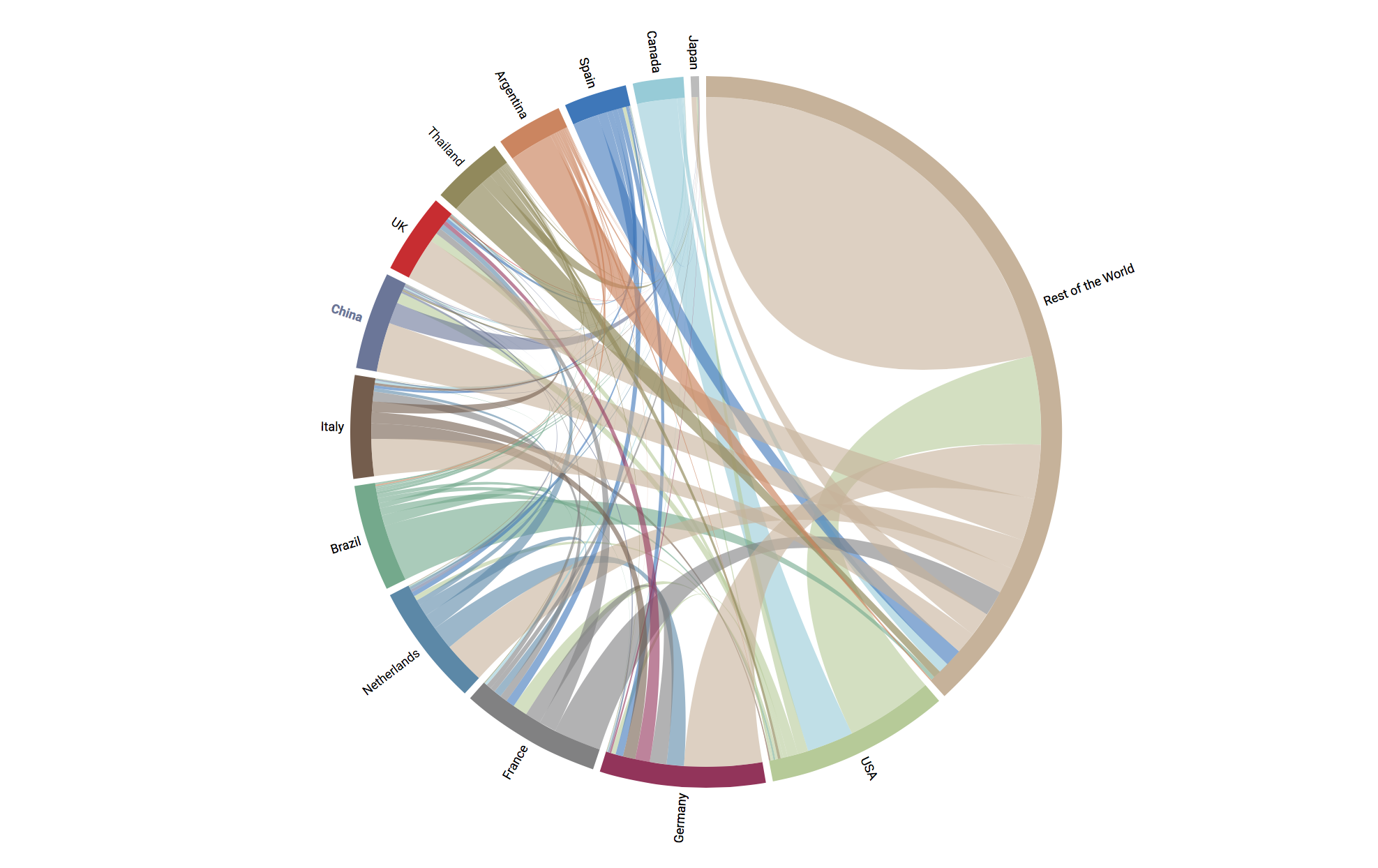

Founded in 1883, the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA) represents over 700 companies involved in seed production, plant breeding and related industries in North America. According to ASTA, a seed can cross up to six borders between the breeder to the farmer who plants it in the field. The United States exported $1.8 billion in seeds in 2017, $610 million of which went to Canada and Mexico.

The global seed market was an estimated $66.9 billion in 2018 and expected to reach $98.1 billion by 2024. According to the International Seed Federation, the Eastern European countries of Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland are the largest exporters of seeds for field crops after France and the United States.

Good Genes

Despite a robust seed trade, the Food and Agriculture Organization worries about the steady loss of biodiversity for food and agriculture. Through a network of more than 1,750 gene banks, the Global Crop Diversity Trust supports a global seed conversation system to ensure a diversity of genetic resources from the ancient, traditional and heirloom varieties to the raw genetic material needed to breed nutrition-packed, high yield, weather- and pest-resistant modern crops.

Seeds can be made available from the gene banks to help farmers recover from natural disasters. After Hurricane Maria devasted 80 percent of Puerto Rico’s crop value, farmers turned to the Tropical Agriculture Research Station run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for seeds and tree grafts to replenish their farms.

One of the largest seed collections resides in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, nestled inside a mountain on an island halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. It houses over 983,500 seeds with room to conserve 4.5 million varieties.

Seed conservation is about more than saving for a rainy day. Food production around the world depends on the availability and international trade in seeds. According to the Global Crop Diversity Trust, many countries strongly depend on crops whose genetic diversity originates from foreign regions, both in their food supply and in their production systems.

So while we should all be thankful that gene banks preserve our food heritage, it’s the free movement of seeds in trade that helps protect today’s food production and supply. Now, if we can only get the stores to carry those Golden Globe pomegranates.

Andrea Durkin is the Editor-in-Chief of TradeVistas and Founder of Sparkplug, LLC. Ms. Durkin previously served as a U.S. Government trade negotiator and has proudly taught international trade policy and negotiations for the last fifteen years as an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University’s Master of Science in Foreign Service program.