The Rise of Global Value Chains (GVCs)

Modern production is increasingly organized around “value chains.” A value chain describes the set of tasks required to bring a product to market, from invention to final use. Thanks to technology and policy improvements, activities such as design, production process development, manufacturing, logistics, marketing, and distribution can be performed by different firms in different places yet subject to precise coordination among the parties. Economists sometime describe this as “trade in tasks,” and the operation and development of global value chains (GVCs) has important implications for trade, investment, innovation, and regulatory policies.

“Companies used to make things primarily in one country. That has all changed. Today, a single finished product often results from manufacturing and assembly in multiple countries, with each step in the process adding value to the end product.” World Bank

While manufacturers have long used specialized suppliers, information and communication technology (I/CT) in the form of cheaper and more reliable telecommunications, information management software, and powerful personal computers have radically lowered the cost of coordinating complex tasks within and between firms over long distances. Fast, inexpensive I/CT makes many more goods and services tradable, and has opened the possibility for efficiency gains through specialization. Trade liberalization (especially lower tariffs) has further reduced trade costs, as have advances in transport—containerized shipping, standardization, and inter-modal transport systems.

This implication is that the many functions that were once housed in one manufacturing plant are now spread across different firms in different places interacting through international trade because it’s cheaper and more efficient to do it that way thanks to these new technologies. GVCs allow firms to look at relative costs and factor endowments (who’s best to do what) and build a set of production arrangements with product and service suppliers depending on whether it makes sense to source these inputs from within and outside the firm’s direct operations.

Increasing specialization and access to global suppliers is what drives economies of scale and scope, which ultimately improves both firm competitiveness and consumer welfare. Companies get better at making more and better things and we like the non-stop innovation and variety of things to buy.

The Apple iPhone is a relatively famous example of a GVC: the device is invented, designed, and developed in Cupertino, California. Its components are sourced from suppliers in the United States and all over the world with final assembly in China by a firm headquartered in Taiwan. The finished devices are distributed all over the world with branding (and, in some cases, retail sale) by Apple.

GVCs operate in many sectors, from apparel to food. The level of specialization varies, but all GVCs rely on low coordination costs, open markets, and efficient transportation.

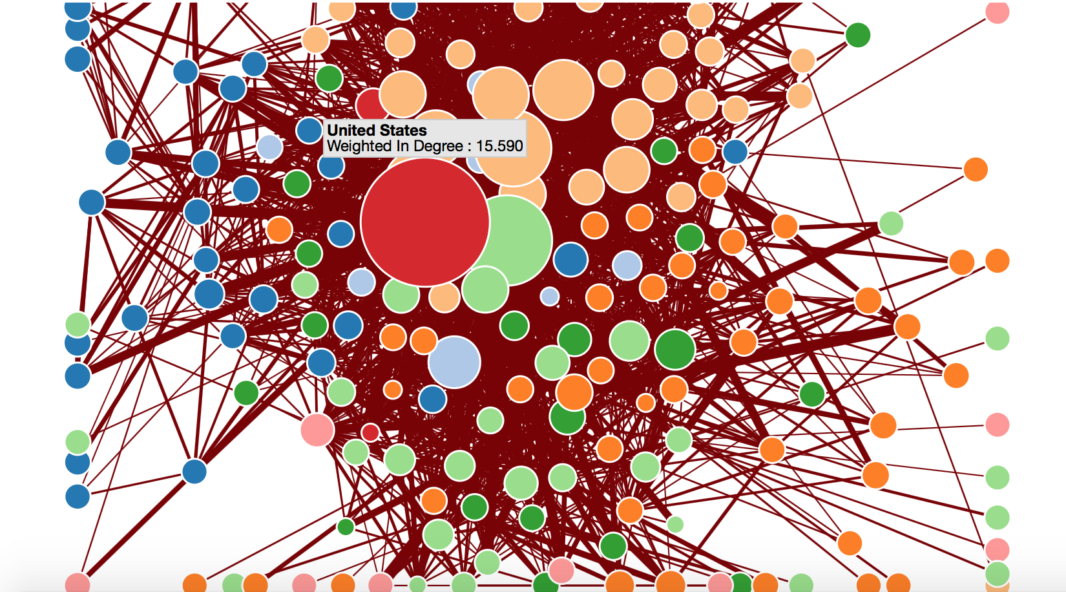

GVCs operate in many sectors, from apparel to food. The level of specialization varies, but all GVCs rely on low coordination costs, open markets, and efficient transportation. Importantly, international trade to a large degree is driven by trade among firms within GVCs. That means that imports of goods and services are the vital backbone of efficient GVCs.

More Resources

- OECD on Global Value Chains: https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/global-value-chains.htm

- Joint OECD-WTO Initiative on Measuring Trade in Value Added: https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/measuringtradeinvalue-addedanoecd-wtojointinitiative.htm

- Mapping Global Value Chains: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/5k3v1trgnbr4.pdf?expires=1478732683&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=DE4E6345A8C097CDD337BFB8DD60443F

Scott Miller is a senior adviser at CSIS. Previously, Miller was director for global trade policy at Procter & Gamble. He advised the U.S. government as liaison to the U.S. Trade Representative’s Advisory Committee on Trade Policy and Negotiations, as well as the State Department’s Advisory Committee on International Economic Policy. Earlier in his career, he was a manufacturing, marketing, and government relations executive for Procter & Gamble in the United States and Canada.