This Trade Agreement Could Cut Your Monthly Utility Bill

Invisible Savings from Trade Can Lower Energy Bills

According to a new study, reducing tariffs on LED light bulbs by 3.6 percent would save American households $320 million each year. How? Lowering the tariff on imported LED bulbs makes it cheaper to buy them. Lower prices also raises demand, leading to greater usage. Using more energy efficient light bulbs could cut electric bills by $129.6 million and lower the number of kilowatt hours in the United States by 238 million every year.

Economist Christine McDaniel and her colleagues applied data from the U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey to estimate the benefits to American households when tariff cuts on the household goods included in the WTO Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) lower the price paid by consumers.

The Biggest Savings Go To Southerners, and Two-Person, Lower Income Households

Using a sample size of 12,175 households, they found that Americans could save as much as $845 million if the cost of some common energy-saving products was reduced.

McDaniel estimates the likelihood that consumers will substitute energy-intensive products for energy-efficient products if the price is lowered. Use of energy efficient products yields energy savings in the form of lower bills or perhaps less money spent on gas to commute in a car. The benefits are not the same for every household, and this is where McDaniel’s analysis gets even more interesting.

For example, the average U.S. household spends $69.51 per year on LED light bulbs, but when you break it down further, you find that a household with one person spends $40.67 and a household of four spends $85.65. Disaggregating the data shows how different households fare under the proposed trade agreement.

People in South would save $268 million, which is more than the amount saved by people in the West ($221 million), Midwest ($186 million), or Northeast ($101 million) of the country. Households with two people achieve the biggest savings, though everyone stands to gain regardless of whether you live alone or with more than five people.

People who own their houses but carry a mortgage would save more than owners without a mortgage. Although the overall amount saved is higher for people with an income of $70,000 or greater, the effect of savings is twice as great for families with incomes of up to $30,000 because spending on energy saving products occupies a larger share of their household budgets.

A Trade Deal for Light Bulbs, Bicycles, and Turbines?

The effort to negotiate a trade deal focused on environmental technologies is an example of how we can make progress to open markets in the absence of a comprehensive global agreement covering all types of goods and services. Forty-six WTO members would agree to the commitments but the benefits would extend to all members.

However, the EGA’s critics in the environmental community say the agreement won’t achieve significant global reductions in emissions because tariffs are not the most significant barrier to widespread industrial uptake of technologies. On principle, the agreement’s supporters say it’s important to show that trade agreements can promote environmental outcomes. On principle, the agreement’s detractors say it is not a good precedent to make value judgments about traded goods.

Traded products are classified using the uniform language of the Harmonized System of Tariff Classification, which describes the physical characteristics of the product. The EGA incorporates the Harmonized System but takes it a step further as negotiators agree on what is an environmental good and therefore included in the scope of the negotiation.

Aaron Cosbey of the International Institute for Sustainable Development points out the challenges to making that cut when he asks, “Are green goods those that are created in a green way (e.g., organic foods)? Are they goods that, in their use or disposal, perform better than most of their substitutes (e.g., efficient refrigerators, wind turbines)? Or are they goods whose purpose is environmental protection (e.g., equipment for monitoring pollution)?” Disagreement over these questions is the reason the deal hasn’t been concluded yet.

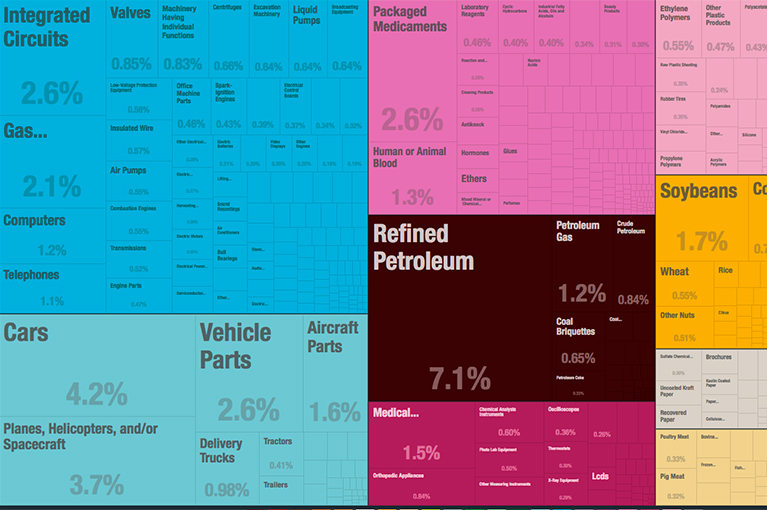

Energy-Saving Products in Your House

The EGA list of so-called “green goods” consists mainly of parts, machines, or technologies that have large-scale industrial application. The list of some 300 items is not public, but taking examples from the list generated by the Asia Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), it includes things like blades and hubs to make wind turbines, water purifying equipment, technologies to destroy hazardous waste, solar batteries, and instruments to measure, record and analyze environmental samples.

Global trade in environmental technologies is expected to double from $1.1 trillion in 2012 to $2.5 trillion in 2022. This is good for companies like GE who make wind turbines and the many American companies that make and use environmental technologies in their facilities all over the world.

But the EGA also includes products people buy for use in their homes like automatic thermostats, gas and electricity meters, LED bulbs, and even bicycles, which is where you can see more immediate savings.

Making Trade Personal

When we calculate the impacts of a trade agreement, the economic models ordinarily used analyze the economy-wide or overall net effect on the average “representative” household. These models produce impressively big but impersonal numbers that people find it hard to wrap their minds around and that fail to produce a feeling the agreement is good for them personally.

It stands to reason that households of different incomes, whether renters or owners, whether located in the northeast or southwest, and whether located in urban or rural areas will behave differently in the buying patterns and expenditures.

As McDaniel’s research demonstrates, trade isn’t just about gaining the opportunity to buy stuff at lower costs. It can be about gaining the opportunity to buy stuff that both costs less and saves you money through their use. And, we can apply additional data to learn how individual households are affected by trade agreements. This is a methodology that is even more relevant to goods we buy in greater volumes or more frequently like clothes and food, and could help us better appreciate the individual benefits of trade agreements.

Negotiators were hopeful they could conclude the EGA this week in Geneva, but after eighteen rounds of talks, China introduced a new list of items they wanted to include and now the negotiators need more time to analyze China’s request. Despite the potential policy downsides, it seems clear that without the EGA, American households will lose a discount on energy-saving products for their house and the chance to lower their household energy bill.

Read Christine McDaniel’s Study: The Environmental Goods Agreement: How will U.S. households fare?

Andrea Durkin is the Editor-in-Chief of TradeVistas and Founder of Sparkplug, LLC. Ms. Durkin previously served as a U.S. Government trade negotiator and has proudly taught international trade policy and negotiations for the last fifteen years as an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University’s Master of Science in Foreign Service program.