The Sobering Reality of a Tariff War

Here comes the expected tariff retaliation.

Running out the clock on a temporary exemption, the Trump administration moved ahead on June 1 with a 25 percent tariff on steel and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum on imports from Canada, Mexico, and the European Union among other significant producers.

Tariff “wars” take on the dynamic of an arms race. Countries build up an arsenal by amassing lists of products where additional tariffs would make a serious dent in the other country’s exports and often include products that are manufactured in the districts of key politicians to get their attention. Fully armed on both sides, countries most often back down or repeal the new tariffs quickly, given the possibility of mutually assured destruction (no need for a bunker on the trade front but there will be direct costs to producers and consumers).

There is plenty of collateral damage in a tariff war because the one-upmanship spills over beyond the sectors named in the original complaint (steel, aluminum, solar panels, washing machines, autos), sweeping in producers like farmers for maximum political effect. The other dirty little secret in tariff wars is that they provide cover for governments to protect the producers of products facing normal market competition. That’s what might just be motivating our closest trading partners to put American whiskey on their lists for tariff retaliation.

I’ll Take (a) Manhattan

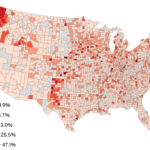

Last year, American makers exported $1.6 billion worth of distilled spirits – 69 percent of those sales were of American whiskies. American spirits are sold in some 130 countries. Canada, the UK, Australia, Germany, and Spain buy the most. Is it possible that Canadian, Scottish, and Irish distillers or the black corn-based Mexican whiskey producers see an opportunity to leverage this tariff war to slow down the explosive growth of American whiskies around the world?

The industry’s top objective for NAFTA re-negotiations was a defensive one: preserve duty-free treatment for U.S. distilled spirits exports. But now, in response to new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from Canada and Mexico, both governments have released a list of U.S. products against which they intend to apply tariffs. Mexico’s list is comprised of $3 billion in tariffs and includes U.S. pork products, apples, cranberries, cheese, potatoes – and whiskey.

Canada has said it will raise tariffs to 25 percent on nearly $13 billion worth of U.S. exports. Its list includes yogurt, coffee, candy, maple syrup, jams, nuts, ketchup – and whiskey. Europe was not exempt from the steel and aluminum tariffs either. In response, Europe’s list of around 200 American goods that might face a 25 percent tariff includes orange juice, corn, tobacco, rice, beans, peanut butter – and whiskey. China is of course at the center of U.S. complaints on steel and aluminum. China’s list of tariffs on U.S. goods includes soybeans, corn, cotton, sorghum, wheat, beef, dried cranberries, orange juice – and whiskey.

That’s the Spirit

Putting together retaliatory tariff lists is an arcane art form in the trade policy world. It’s two parts economic analysis and one part just “hit ‘em where it hurts”. Once you start a tariff war, you cannot contain which of your prized industries will get caught in the crosshairs. This time, it’s sure to be American whiskies.

American author Bernard DeVoto wrote in The Hour, “In the heroic age our forefathers invented self-government, the Constitution, and bourbon…Our political institutions were shaped by our whiskeys…and share their nature. They are distilled not only from our native grains but from our native vigor, suavity, generosity, peacefulness, and love of accord.”

We will need to draw on these values and characteristics get us – and our whiskies – through this tariff war as quickly as possible.

Andrea Durkin is the Editor-in-Chief of TradeVistas and Founder of Sparkplug, LLC. Ms. Durkin previously served as a U.S. Government trade negotiator and has proudly taught international trade policy and negotiations for the last fifteen years as an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University’s Master of Science in Foreign Service program.